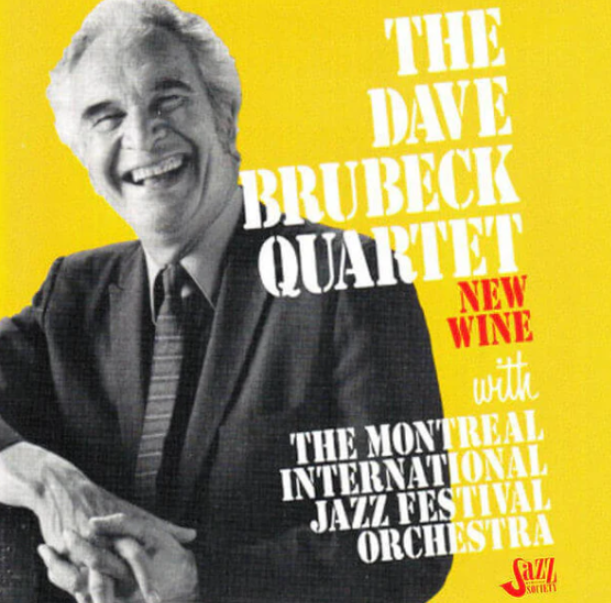

Dave Brubeck’s New Wine: A Historic Jazz Collision at the Montreal International Jazz Festival

There are music festivals, and then there’s the Montreal International Jazz Festival. For decades, it’s turned the entire city into a multi-stage concert, where you hear jazz from cafes to cathedrals, street corners to grand concert halls. Leonard Feather, one of jazz’s most respected voices, once called it the finest of its kind. And in 1980s Montreal, something audacious happened that lived up to the hype-Dave Brubeck brought his quartet to town and agreed to do what no one else had done: pair a jazz combo with members of the Montreal Symphony to create a live recording unlike any other called “New Wine.”

The result? A televised concert that felt more like a tightrope walk than a performance. With only three hours of rehearsal and zero guarantees, Brubeck led his quartet into uncharted territory. That concert became the heart of the New Wine recording-a rare capture of jazz in full flight, lifted by orchestral strings, driven by the rhythm section, and all of it held together by sheer guts and intuition.

The Festival That Took Over an Entire City

The Montreal International Jazz Festival isn’t just another date on the jazz calendar. It’s a musical takeover. Every summer, the city transforms into one giant performance space, blurring the lines between audience and artist. Concert halls host legends. Parks echo with brass and sax. Sidewalks fill with spontaneous solos. It’s the kind of place where even a walk to the coffee shop feels like a jazz pilgrimage.

Started in 1980, the festival was the brainchild of producers Alain Simard and Andre Menard. They didn’t just want another jazz fest-they wanted a cultural movement. Their bookings always leaned bold, often bringing in musicians who didn’t play it safe. So when they pitched an idea to Dave Brubeck involving orchestral backing at a live concert, they weren’t surprised when he said yes. But even they didn’t know how powerful that yes would become.

Brubeck Gets the Call: “Let’s Add a Symphony”

Brubeck was no stranger to stretching jazz beyond its norms. He'd already made waves with odd time signatures, classical motifs, and a refusal to stick to jazz orthodoxy. So when Simard and Menard suggested combining his quartet with members of the Montreal Symphony Orchestra, it wasn’t that far-fetched-for Brubeck, anyway.

The challenge wasn’t in saying yes. It was pulling it off. This wasn’t a studio gig. It was live, with an unfamiliar orchestra, in front of thousands of jazz purists, with CBC cameras rolling. But Brubeck accepted with excitement, knowing the risk was part of the magic.

Three Hours. No Prior Rehearsal. No Safety Net.

Imagine walking into a room with an orchestra you've never met, handing them jazz charts, and having just three hours to build chemistry. That was the setup. And no, there was no dress rehearsal the night before. Just one chaotic afternoon, Russell Gloyd at the conductor's podium, and a hope that it would all come together.

Russell Gloyd, Brubeck’s longtime musical director, played a crucial role in managing the balance. He acted as the bridge between the quartet's improvisational instincts and the orchestra’s precision. What resulted from that short burst of preparation was nothing short of miraculous-a fully realized concert that sounded as if they'd been touring together for years.

Televised on the CBC: The Night Jazz Took Over the Airwaves

The performance wasn’t just a festival highlight. It became a nationally televised event, broadcast live on the CBC. That meant more than just pressure for the musicians-it meant capturing a jazz experiment in real time, with no edits, no fixes, no post-production cleanups.

Months later, Brubeck watched the video. What he saw wasn’t just a good show. It was a moment. He knew instantly that the music had to live beyond a single airing. That’s when the idea for New Wine began to ferment.

What Made New Wine Worth Bottling

Brubeck had no intention of letting this concert be forgotten. The audio was too alive, too raw, and too meaningful. New Wine became the bottled version of that night, straight from the CBC’s live broadcast soundtrack. It wasn’t cleaned up or overproduced. It didn’t need to be.

The energy of the crowd, the interaction between soloists and symphony, the moments of unplanned brilliance-they all made it onto the album. It wasn’t perfect, and that’s exactly why it mattered.

Meet the Quartet: Bill Smith, Chris Brubeck, Randy Jones

Brubeck’s quartet at this point wasn’t the classic Time Out crew, but it was just as impactful. Clarinetist Bill Smith brought a lighter, reedier sound than Paul Desmond’s alto sax, but it had its own sharp character. Smith had a way of letting notes drift, giving the music space to breathe.

Chris Brubeck, Dave’s son, laid down electric bass lines that were less about walking and more about groove. His rhythmic intuition locked in tightly with drummer Randy Jones, who had the impossible job of keeping both the orchestra and the quartet in sync-and did it with ease.

This lineup wasn’t just playing together-they were listening hard, taking risks, and making sure no note went to waste.

The Setlist: Brubeck Originals and One Iconic Standard

The concert featured six Brubeck compositions that showed off the band’s range and creativity. Blue Rondo à la Turk was a standout-its mix of 9/8 and 4/4 rhythm is a playground for jazz phrasing. The orchestra handled it without hesitation.

Koto Song gave the concert a quieter, meditative break, drawing from Japanese tonalities Brubeck had absorbed during his travels. The orchestral strings added depth to the composition’s reflective nature.

And then there was Take the 'A' Train. While not a Brubeck original, it was a deliberate choice. A nod to Duke Ellington, it reminded everyone that while Brubeck was pushing boundaries, he never forgot the masters who laid the tracks.

The Role of the Orchestra: Enhancement, Not Interference

Orchestral jazz collaborations can go sideways fast. Too many strings, and you lose the swing. Too little structure, and the symphony sounds lost. But here, Russell Gloyd struck a balance. The arrangements gave space for improvisation, while the symphony added harmonic layers that elevated the compositions.

Members of the Montreal Symphony proved adaptable and surprisingly loose. They didn’t weigh the music down. Instead, they lifted it up-responding to solos, swelling during climaxes, and never overstaying their welcome.

Why New Wine Still Stands Out in Brubeck’s Catalog

Brubeck recorded dozens of albums, many with tighter polish and more famous songs. But New Wine stands alone for its daring. This wasn’t just jazz with strings. It was risk taken live, with no second take.

It reflects everything Brubeck stood for: improvisation, collaboration, global influences, and musical integrity. It's also one of the best examples of how jazz can evolve without losing its soul. Stream it now, only at Musical Heritage Society.