Collection: GEORGE ANTHEIL (1900-1959)

George Antheil (1900-1959) remains one of the most enigmatic and multifaceted figures in 20th-century American music. A composer, pianist, author, and surprisingly, an inventor, he burst onto the European avant-garde scene as a self-styled "Bad Boy of Music" before forging a later career as a successful Hollywood film composer. His life was a study in contrasts, marked by audacious experimentation, public notoriety, and unexpected shifts in direction.

Born George Johann Carl Antheil in Trenton, New Jersey, he displayed early musical talent. After studies with notable teachers like Constantin von Sternberg and Ernest Bloch, the ambitious young pianist-composer set his sights on Europe in 1922. He initially landed in Berlin but soon gravitated to the vibrant artistic hub of Paris in the 1920s. Immersing himself in the modernist milieu, he associated with figures like Ezra Pound, James Joyce, Erik Satie, Fernand Léger, Man Ray, and Igor Stravinsky, whose Rite of Spring premiere riot served as a model for Antheil's own provocative aspirations.

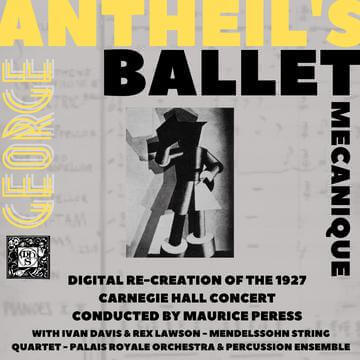

Antheil cultivated an image as a radical futurist, championing machine-age aesthetics. His piano recitals often featured his own dissonant, percussive works and were sometimes staged to incite controversy, reportedly even placing a loaded pistol on the piano for protection against hostile audiences. This period culminated in his most infamous and arguably most significant work: Ballet Mécanique (1924). Originally conceived to accompany a Dadaist film by Fernand Léger and Dudley Murphy (though synchronization proved impossible with the technology of the day), the piece was scored for an ensemble including multiple player pianos, airplane propellers, electric bells, sirens, and percussion. Its 1926 Carnegie Hall premiere in New York, featuring an amplified and expanded orchestration, was a scandalous succès de scandale, cementing Antheil's notoriety but also proving financially ruinous and difficult to replicate.

The intense, often cacophonous, style of Ballet Mécanique represented the peak of his early radicalism. Following its mixed reception and the waning of Parisian ultra-modernism, Antheil began to temper his approach. He returned to the United States, seeking more stable compositional ground. He experimented with neoclassicism and composed operas like Transatlantic (1930) and Helen Retires (1934), which, while innovative, struggled to find lasting places in the repertoire.

Facing financial difficulties, Antheil made a significant career pivot in the mid-1930s, moving to Hollywood to become a film composer. Here, he found considerable success, proving remarkably adaptable. He scored dozens of films across various genres, including notable works like The Plainsman (1936), Knock on Any Door (1949), Dementia (1955), and The Pride and the Passion (1957). While his film music was often more conventional than his concert works, it displayed craftsmanship and dramatic flair.

Perhaps the most surprising chapter in Antheil's life unfolded during World War II. Collaborating with the Austrian-born Hollywood actress Hedy Lamarr, who possessed a keen inventive mind, they developed and patented (in 1942) a "Secret Communication System." This ingenious concept used a mechanism based on player piano rolls to rapidly switch radio frequencies, creating a frequency-hopping spread spectrum signal designed to prevent enemy interception or jamming of radio-guided torpedoes. While the U.S. Navy initially shelved the complex technology, the core principles behind their invention later proved fundamental to the development of secure military communications, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and GPS technology.

In his later years, alongside his film work, Antheil returned to concert composition, producing several symphonies and other orchestral pieces in a more accessible, tonal style. He also penned a lively, if not always strictly factual, autobiography, aptly titled Bad Boy of Music (1945).

George Antheil died in New York City in 1959. His legacy is complex: the brash innovator whose Ballet Mécanique remains a landmark of musical modernism; the pragmatic film composer who mastered Hollywood's demands; and the unlikely inventor whose wartime collaboration with Hedy Lamarr had unforeseen technological repercussions. He was a restless talent, forever exploring new avenues, leaving behind a body of work as diverse and contradictory as the man himself.