1

/

of

1

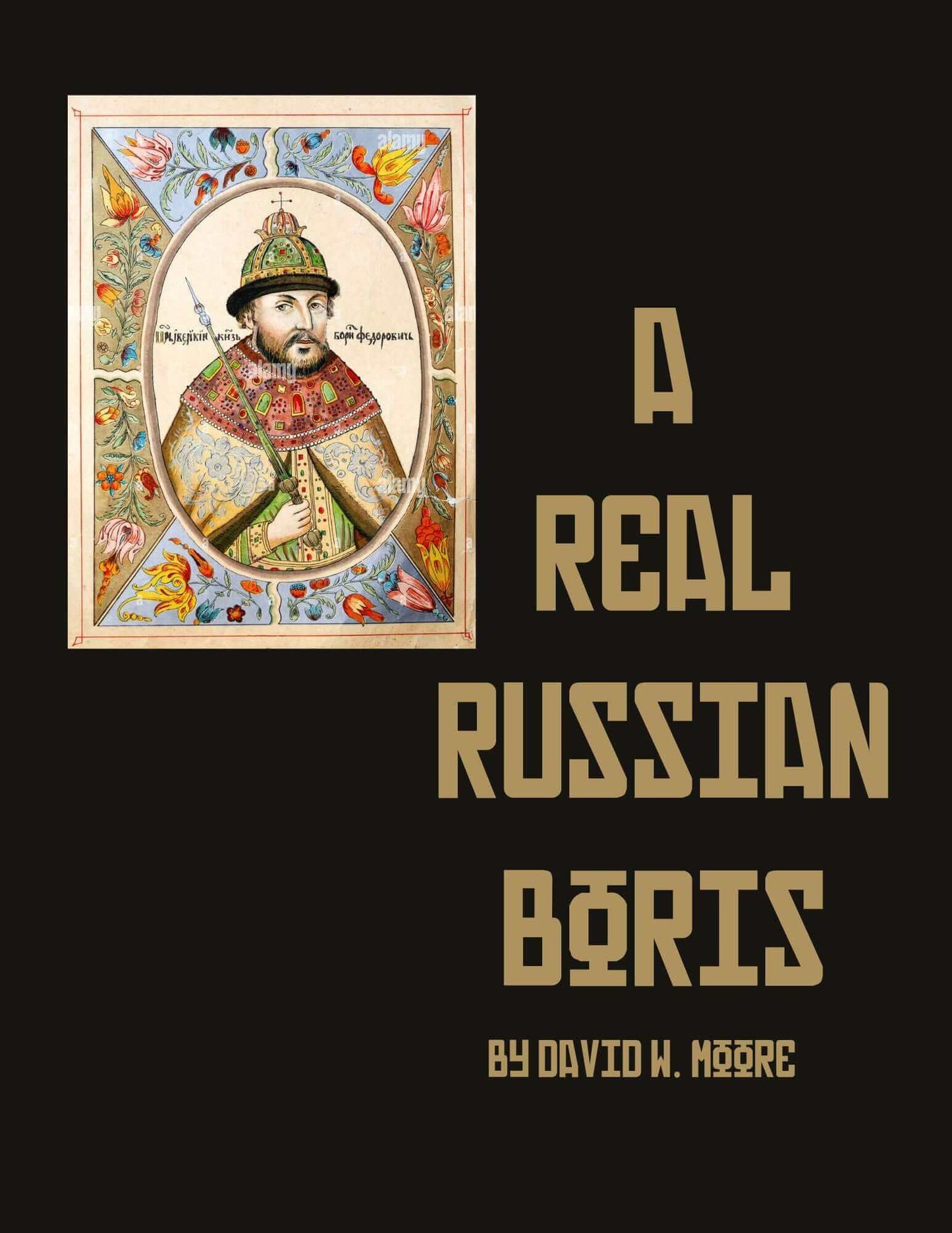

A Real Russian Boris

A Real Russian Boris

Regular price

$0.00

Regular price

Sale price

$0.00

Unit price

/

per

The MHS Review 237 Vol. 3, No. 3 March 26, 1979

00:00

/

00:00

•

skip_previous

play_circle_outline

pause_circle_outline

skip_next