1

/

of

1

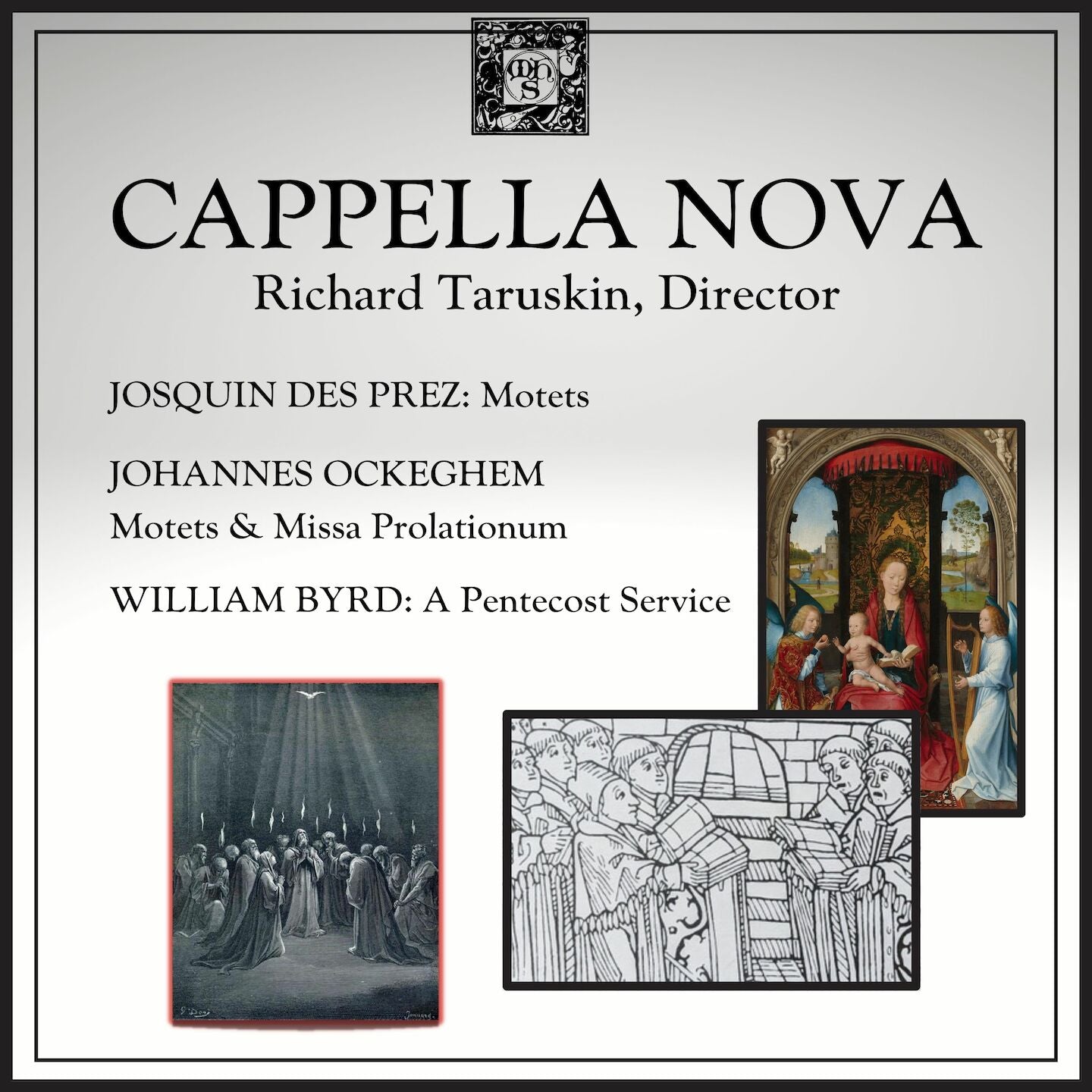

CAPPELLA NOVA: THE MUSICAL HERITAGE SOCIETY RECORDINGS

CAPPELLA NOVA: THE MHS RECORDINGS - Cappella Nova, Richard Taruskin, director

CAPPELLA NOVA: THE MHS RECORDINGS - Cappella Nova, Richard Taruskin, director

All of Cappella Nova's Musical Heritage Society recordings in one download. As an added bonus, the liner notes contain all of the notes written by the respected classical music historian, Richard Taruskin.

Regular price

$9.99

Regular price

$9.99

Sale price

$9.99

Unit price

/

per

$5.00

MHS

MHS EXCLUSIVE DIGITAL DOWNLOAD

All of Cappella Nova's Musical Heritage Society recordings. As an added bonus, the liner notes contain all of the notes written by the respected classical music historian, Richard Taruskin.

Performers

00:00

/

00:00

•

skip_previous

play_circle_outline

pause_circle_outline

skip_next

Also Available from CAPPELLA NOVA: THE MUSICAL HERITAGE SOCIETY RECORDINGS

-

Members Save 50% MHS EXCLUSIVE DIGITAL DOWNLOAD

CAPPELLA NOVA: THE MHS RECORDINGS - Cappella Nova, Richar...

ExploreRegular price $9.99Regular priceUnit price / per$9.99Sale price $9.99 -

Members Save 50% DIGITAL DOWNLOAD with LINER NOTES

JOSQUIN DES PREZ: MOTETS FOR THE BLESSED VIRGIN - Cappell...

ExploreRegular price $9.99Regular priceUnit price / per$9.99Sale price $9.99 -

Members Save 50% DIGITAL DOWNLOAD with LINER NOTES

Ockeghem: Prince of Music - Cappella Nova, Richard Tarusk...

ExploreRegular price $9.98Regular priceUnit price / per$9.98Sale price $9.98 -

Members Save 50% DIGITAL DOWNLOAD with LINER NOTES

Ockeghem: The Motets - Cappella Nova, Richard Taruskin, d...

ExploreRegular price $9.99Regular priceUnit price / per$9.99Sale price $9.99 -

Members Save 50% DIGITAL DOWNLOAD with LINER NOTES

Veni Sancte Spiritus: A Pentecost Service by William Byrd...

ExploreRegular price $9.99Regular priceUnit price / per$9.99Sale price $9.99