1

/

of

1

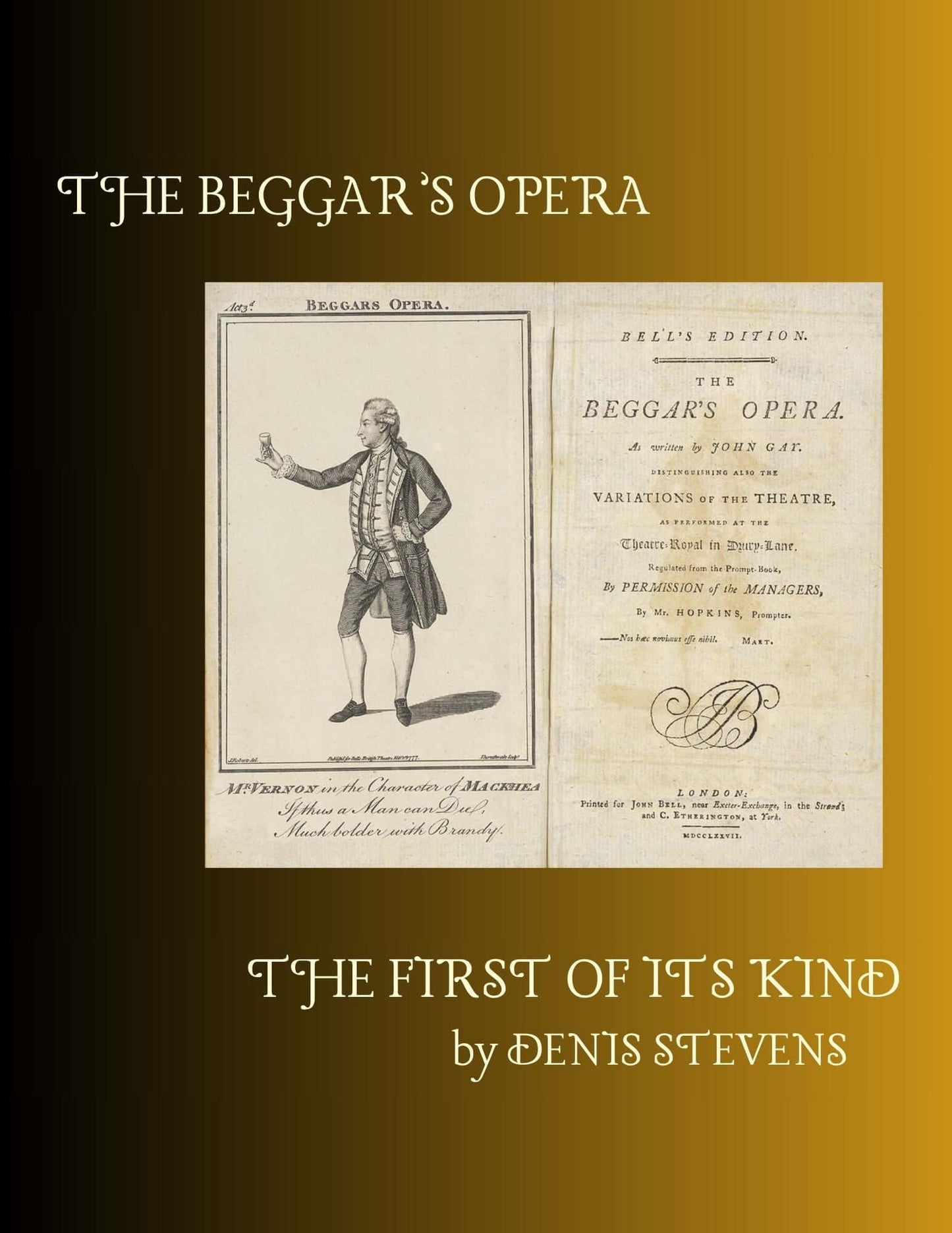

ESSAY: The Beggar's Opera--First of It's Kind

ESSAY: The Beggar's Opera--First of It's Kind

Regular price

$0.00

Regular price

Sale price

$0.00

Unit price

/

per

The MHS Review 238 Vol. 3, No. 4 • April 16, 1979

00:00

/

00:00

•

skip_previous

play_circle_outline

pause_circle_outline

skip_next