Collection: SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891-1953)

Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev (1891-1953) remains one of the most significant and frequently performed composers of the 20th century. A figure of striking contradictions, his music embodies a unique blend of modernist dissonance, driving rhythms, classical clarity, and deeply felt lyricism, reflecting a life lived across turbulent political and artistic landscapes.

Born in Sontsovka, Ukraine (then part of the Russian Empire), Prokofiev was a child prodigy. Encouraged by his pianist mother, he composed his first opera at age nine and entered the prestigious St. Petersburg Conservatory at thirteen. Here, studying under luminaries like Rimsky-Korsakov and Lyadov, he quickly established himself as a brilliant, albeit rebellious, talent. His early works, including the explosive Scythian Suite and the percussive Piano Concertos Nos. 1 and 2, shocked conservative audiences with their "barbaric" energy, sharp dissonances, and motoric drive, earning him the reputation of an enfant terrible.

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, Prokofiev sought creative freedom and opportunities abroad. He spent nearly two decades living and working primarily in the United States and Paris. This period saw the creation of diverse and important works, including the popular opera The Love for Three Oranges, commissioned by the Chicago Opera, and several ballets for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, such as Chout, The Steel Step, and the profoundly moving The Prodigal Son. During these expatriate years, Prokofiev toured extensively as a virtuoso pianist, performing his own demanding compositions. While his modernist edge remained, elements of neoclassicism and a growing lyrical warmth began to temper his earlier ferocity.

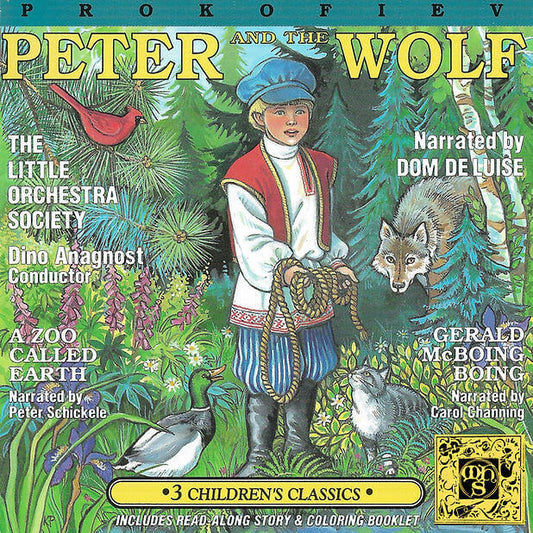

Despite international success, Prokofiev felt increasingly homesick and perhaps underestimated the changing political climate in his homeland. In 1936, drawn by promises of commissions and a longing for Russian soil, he made the momentous decision to return permanently to the Soviet Union. Initially, this move yielded a period of extraordinary creativity. He produced some of his most beloved and enduring masterpieces: the evocative ballet Romeo and Juliet, the charming symphonic fairy tale Peter and the Wolf, the monumental film score and cantata Alexander Nevsky (in collaboration with director Sergei Eisenstein), and the powerful Symphony No. 5.

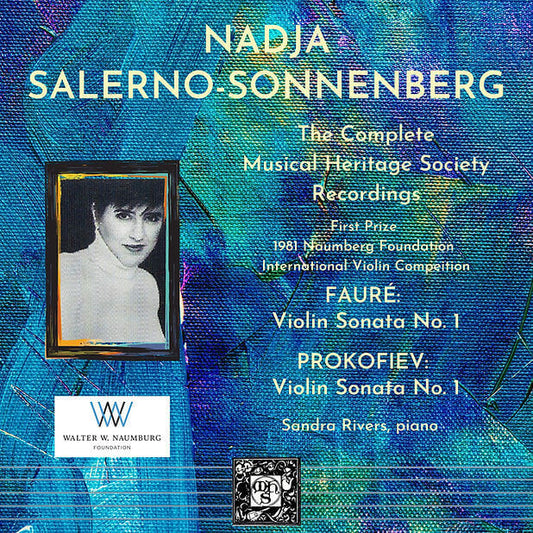

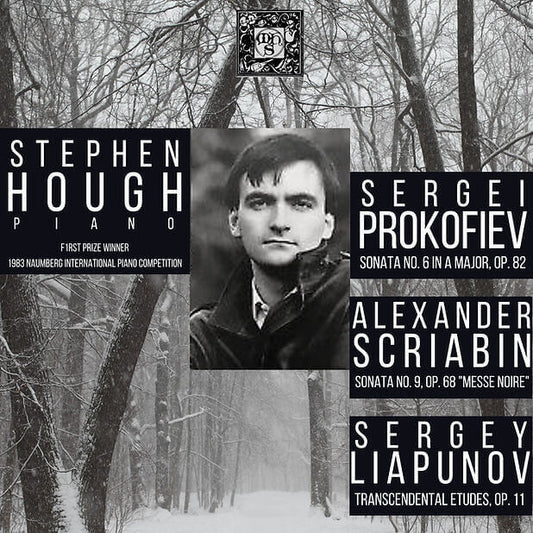

However, navigating the artistic constraints of Stalin's regime proved increasingly perilous. While Prokofiev initially adapted his style, incorporating folk-like melodies and clearer structures aligning somewhat with the doctrine of Socialist Realism, his inherent modernism eventually brought him into conflict with the authorities. The Second World War inspired intensely dramatic works like the "War Sonatas" (Piano Sonatas Nos. 6, 7, and 8) and the epic opera War and Peace.

The post-war years were harsh. In 1948, alongside Shostakovich and others, Prokofiev was publicly denounced in the Zhdanov Decree for "formalism" – essentially, for writing music deemed too complex, dissonant, and disconnected from the supposed needs of the Soviet people. This censure severely impacted his health, financial stability, and ability to get works performed. His first wife, Lina Llubera, was arrested and sent to the Gulag. Despite failing health and official disapproval, Prokofiev continued to compose, producing works like the ballet Cinderella and the lyrical Symphony No. 7.

Sergei Prokofiev died on March 5, 1953, ironically on the same day as Joseph Stalin. His death was largely overshadowed by the dictator's demise. Yet, his legacy endures. Prokofiev left behind a vast and varied body of work across nearly every genre. His unique musical language – characterized by its sharp wit, rhythmic vitality, unexpected harmonic shifts, soaring melodies, and brilliant orchestration – continues to captivate audiences worldwide, securing his place as a vital and complex master of 20th-century music.