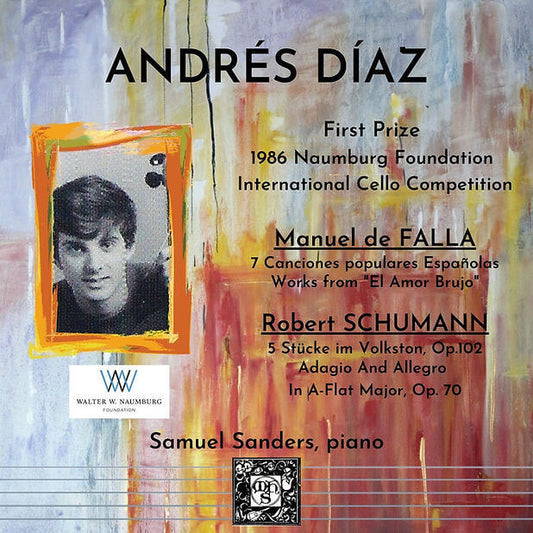

Collection: ROBERT SCHUMANN (1810 – 1856)

Robert Schumann (June 8, 1810 – July 29, 1856) remains one of the most quintessential composers of the Romantic era, a figure whose life and music profoundly embody the period's ideals of intense personal expression, literary inspiration, and the convergence of art forms. A brilliant pianist, influential music critic, and endlessly imaginative composer, Schumann's work, particularly for piano and voice, delves into the depths of human emotion with unparalleled sensitivity and psychological insight.

Born in Zwickau, Saxony (Germany), Schumann was immersed in literature from a young age, thanks to his father, a bookseller and publisher. This literary background deeply influenced his musical imagination throughout his life. Initially pushed towards law studies by his mother after his father's death, Schumann's passion for music, particularly the piano, proved irresistible. In 1830, he moved to Leipzig to study piano intensively with the renowned teacher Friedrich Wieck, harboring ambitions of becoming a concert virtuoso.

However, these ambitions were tragically cut short. Likely due to a combination of overzealous practice and a finger-strengthening device, Schumann suffered a debilitating injury to his right hand around 1832, making a virtuoso career impossible. This setback proved paradoxically fruitful, as he redirected his immense creative energies entirely towards composition and music criticism. In 1834, he co-founded the influential journal Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (New Journal for Music), becoming its editor and chief contributor. Through this platform, he championed composers he admired (famously hailing Chopin and later Brahms) and crusaded against the shallow virtuosity he perceived in much contemporary music. He often wrote under pseudonyms representing different facets of his own personality: the fiery, impulsive Florestan and the gentle, introspective Eusebius, reflecting the duality present in his own music.

During this period, Schumann fell deeply in love with his teacher's daughter, Clara Wieck, already a brilliant piano prodigy. Friedrich Wieck vehemently opposed the match, leading to a painful and protracted legal battle. Despite Wieck's resistance, Robert and Clara finally married in 1840, on the day before Clara's 21st birthday. Their marriage was a deep personal and artistic partnership, though fraught with challenges, including Schumann's recurring mental health struggles.

The year of their marriage, 1840, is famously known as Schumann's "Liederjahr" or "Year of Song." In an astonishing outpouring of creativity, he composed over 150 songs, including the celebrated cycles Dichterliebe (A Poet's Love) and Frauenliebe und -leben (Woman's Love and Life), and the two Liederkreis collections (Op. 24 and Op. 39). These works revolutionized the genre, creating an equal partnership between voice and piano, exploring subtle psychological nuances, and displaying his profound connection to poetry.

Having conquered the Lied and piano miniature (with masterpieces like Carnaval, Kinderszenen, and Kreisleriana already behind him), Schumann turned his attention to larger forms in the 1840s. He composed orchestral works, including four symphonies (most notably the "Spring" and "Rhenish"), the popular Piano Concerto in A minor (written for Clara), a Cello Concerto, and significant chamber music, including the sublime Piano Quintet and Piano Quartet.

Schumann's later years were marked by increasing mental instability, likely stemming from syphilis contracted in his youth or bipolar disorder. He held positions in Dresden and later as municipal music director in Düsseldorf, but his conducting abilities and mental state deteriorated. A bright moment came in 1853 with the arrival of the young Johannes Brahms, whom Schumann immediately recognized as a genius, proclaiming him music's new chosen one in his final article, "Neue Bahnen" ("New Paths").

In February 1854, Schumann suffered a severe breakdown, experiencing auditory hallucinations and attempting suicide by throwing himself into the Rhine River. He was rescued but, at his own request, was admitted to a private mental asylum in Endenich, near Bonn. He remained there for the final two years of his life, visited only occasionally by Brahms and, shortly before his death, by Clara. Robert Schumann died in the asylum on July 29, 1856.

His legacy is immense. Schumann's music, with its soaring lyricism, intricate rhythms, rich harmonies, and deeply personal, often autobiographical nature, perfectly encapsulates the spirit of German Romanticism. He remains a towering figure in the history of piano music and the art song, and his work continues to move listeners with its profound emotional honesty and imaginative power.